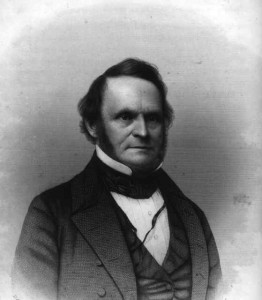

Chauncey Goodrich:

Yale’s Professor of Compassion and Revival |

One Saturday in April 1808, Yale’s students and faculty gathered for their regular evening chapel service. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary, but President Timothy Dwight couldn’t keep his voice from quavering and breaking as he stood to read Scripture that night. When he joined with others to sing a hymn, he faltered through one stanza and stopped.

A spiritual awakening had swept New Haven in recent months, and over two hundred townspeople had repented and believed. The college, though, remained untouched. Yale’s dedication to the Gospel was inscribed in her walls and in her charter, but her students seemed oblivious. An impenetrable deadness seemed to rest on the school.

Overwhelmed that night with a sense of Yale’s spiritual need, Dwight pleaded with God to show mercy and send revival. He preached the next morning on the verse “Young man, I say unto thee, arise!” (Luke 7), warning students not to stay in apathy and rebellion. The deadness in the air lifted, and hardness gave way to conviction of sin. The whole tone of college life changed, and at least thirty students believed before the end of the school year.

One who heard Dwight pray that April was a sophomore, Chauncey Allen Goodrich. There is little doubt it affected him, for he first declared his faith in Christ that spring. He was no stranger to Dwight’s preaching, for as the son of one of Yale’s law professors, he had attended college chapel for the past six years or more. But something changed for him in 1808.

By his own account of events, Goodrich went one day that spring to visit a Christian friend in another room in the college. Drawing near the door, he heard “shouts of laughter” from within. The thought hit him, “These Christians have a right to be happy, but I have not.”1 Sensing that only peace with God could fill the emptiness of his heart, he went back to his room to pray and repent. The void in him was soon replaced by the joy of knowing Christ.

Converted in the city side of the revival were the crusty old skeptic Noah Webster (see sidebar), and his two oldest daughters, Emily and Julia. Here we can see God’s sovereignty, for Julia was to become Chauncey Goodrich’s wife. Sixteen at the time, she offered herself to God in these terms “I … consecrate to thee all I am, or have, the faculties of my mind, the members of my body, my worldly possessions, my time & my influence over others, to be used entirely for thy glory ….”2 The strength of Julia and Chauncey’s marriage was their strong love of Christ.

Epitaph inscription reads:

“Not slothful in business, fervent in spirit,

serving the Lord.”

From the time of his conversion, Chauncey planned to enter the ministry and he studied for it with the help of Timothy Dwight. Julia strongly supported his choice, praying for him fervently. At a youth conference in Durham, Connecticut, Goodrich saw revival break out while he was speaking. A girl in the audience burst out crying, then the entire crowd of sixty dissolved in tears of repentance.3 He spoke nine times more in the following week to those under conviction of sin.

The young man found himself in high demand as a preacher, and eventually, the Park Street Church of Boston, one of the most prestigious congregations in New England, called him to become their pastor.

But trouble came in the form of chronic illness, and Goodrich grew discouraged. He felt physically and spiritually so inadequate to his task, that he wondered at times if he had mistaken his calling. The spread of Unitarianism disheartened him, and he dreaded being asked to take a pastorate in Massachusetts, where that heresy was strongest. When he married Julia and took a post in Middletown, Connecticut, his health proved so fragile that he lasted in his job only a year and a half.

Just then, Goodrich was invited to become professor of rhetoric at Yale, filling part of the position of Timothy Dwight, who had died a few months earlier. This meant giving up pastoring, and the change seemed to a heartbroken Goodrich like a great loss.

But his mother had recently counseled him to ask himself some searching questions about his motives for wanting to serve God. Could he submit from the heart “to serve [the] Lord in a humble, less conspicuous manner” than he had hoped? Was he willing to “acquiesce in the decisions of the Saviour” to “crown [his] efforts with greater or less success” as He determined?4 These questions pared the whole matter of serving the Lord down to the spiritual base line. Was Chauncey pleasing himself, or did he love Jesus?

In the end, Goodrich decided for Yale, though it meant putting aside his heart’s desire to preach. But what seemed like a heavy disappointment, God intended for blessing and expansion, both for Goodrich and for the college.

Academically, Yale needed an overhaul, and one of the first things the new professor did was entirely revamp his department’s curriculum. Because of the old curriculum’s emphasis on Greek and Latin, students up through 1817 had received only minimal instruction in their own language. The new course of study included English grammar and composition and solid training in public speaking. Goodrich felt men should leave Yale gifted to persuade, whether they became public servants, or spokesmen for God. His lectures on rhetoric become famous, and he has been considered America’s only important rhetorical theorist of the nineteenth century.

Rhetoric turned out to be only one of Goodrich’s interests. As Noah Webster’s son-in-law, he began work on the dictionary, which stretched over a lifetime. In 1828, while Webster was struggling to push his first quarto edition through the press, his publisher was badgering him also to produce a cheaper abridgement to sell on the mass market. Feeling overwhelmed with work and under constant financial pressure from the profligacy of his scapegrace son, William, Webster called on Goodrich not only to oversee the abridgement, but also to purchase its copyright. Goodrich consented, and shouldered Webster’s work after he died. His 1847 complete edition was marketed at an affordable six dollars a copy, and according to Webster scholar Harry Warfel, “the presence of a Webster Dictionary in almost every literate household dates from this year.”

Goodrich greatly enhanced the scholarly value of the dictionary by enlisting the help of his colleagues at Yale, and the thesaurus he added to the 1859 edition was the best of its kind. His lexicographic work, though nominally only editorial, was in fact original. Editors for Webster’s monument continued to be drawn from Yale well into the twentieth century.

Though he took up the dictionary work to please Webster, Goodrich’s generosity made him the target of a jealous attack by his brother-in-law William C. Fowler, professor of rhetoric at Amherst. Fowler began his assault in 1845, and wasted much of his life on an energetic campaign to cast doubt on Goodrich’s motives, discredit his scholarship, and claim for himself the editorship of the dictionary and its financial rewards.

The Amherst professor saved his worst for after Goodrich’s death, when he had a pamphlet printed up listing his complaints against the dead. Goodrich’s family wisely refrained from even reading the pamphlet until 1869, and apparently never responded to its contents.

Goodrich’s personal response to Fowler was confined mostly to private meditations, and these show he knew that God was using the bitter barrage for good. In a diary entry made on his birthday in 1845, Goodrich says:

“I cannot doubt that I needed exactly this trial to humble and purify my soul. It is impossible to penetrate the depth of self-complacency … here was the tenderest place in which to touch me. I hope before God I can say … (1) That I have never prayed more fervently for any one than for the author of this attack. My heart warm toward him in prayer … [2] I feel much more dead to worldly things, especially to public estimation. This is what I needed.”5

In the end only Goodrich benefited from the episode, for it persuaded the rest of the family that Fowler was insane. Fowler’s jealousy effectively poisoned his daughter, and she wrote contentious letters to the Webster heirs down to at least 1876, demanding a portion of the dictionary profits. Goodrich had given all his share of the money to advance the Gospel.

Contemporaries uniformly describe Goodrich as a fountain of energy, which is amazing given his susceptibility to migraines and other physical debilities. He literally lived out the verse “And whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not unto men ….” (Colossians 3, KJV) The cord that bound his work together was his spiritual fervor, and nowhere is that better demonstrated than in his interaction with students.

Yale’s college pastor at the time, Eleazar Fitch, could preach well, but was too distant and impersonal to have much impact on students. By contrast, Goodrich was warmhearted and approachable, a person who could help in every kind of need. He had no office or badge, but become shepherd and watchman to generations of Yalies. Theodore Dwight Woolsey remarked that people came from outside Yale to seek Goodrich’s help: “… Probably no man in New Haven was more resorted to as a counselor than he was in the last twenty or twenty-five years of his life.” He was hopeful and gentle, “not breaking the bruised reed or quenching the smoking flax.”6

Early in his career as a teacher, at student request, Goodrich began weekend Bible studies, and continued them through the end of his life. Here, he chatted with students in a natural, practical way, giving them help in their Christian lives, and a Biblical view of current issues. Once a month, the topic was missions. University secretary Franklin Dexter (Yale, 1861), himself no believer, said that even skeptical students made a point of going to these studies, and called them “unquestionably the most efficient religious influence in the College.”7

That Yale remained spiritually vital through the early nineteenth century had much to do with Goodrich’s influence, but his labors were quiet and informal. He prayed with Julia every morning for the college, and the faculty gathered for weekend prayer at his house. Students sought him out for private conversation: in March-April 1846, he led eighteen of them to the Lord.8 Clearly, Goodrich did what Oswald Chambers called “persevering work in the unseen.” Yale experienced revival at least seventeen times during the period 1817-1860, though a full record of these years has yet to surface.

Probably one of the reasons there were so many awakenings at Yale in this time period is that the faculty came to understand Gospel truth in a fresh way. The simplicity of Christ’s invitations to the lost had been obscured by generations of theologians who taught that sinners are incapable of choosing Jesus, and must wait for Him to come to them. Chauncey Goodrich and others rightly saw that this belittled the wooing power of the Holy Spirit, and made nonsense of the plain language of the Scripture.

In his Yale lectures on revival, Goodrich noted that the fanatic excesses and agitation at times evident in the First Great Awakening arose from this paralyzing doctrine of the impotence of the will. “… Men when really awakened were much like persons shut up in a burning house; [the preacher] told them to escape” but took away “any hope in effort.” Goodrich made it his business to open the Gospel door to sinners. He taught not only that the lost could come to Christ, but that God was anxious to restore believers to their first love and give them his Holy Spirit. “… To the Church itself, we can say on the ground of promise [Luke 11], you can have a revival in your own hearts. Every real member of Christ’s body can come back from the world and have the special presence of the Spirit.” When God’s people make a right request, “God is predisposed to grant the exact thing his children pray for … we have therefore is inexpressible encouragement to labor and pray for revival ….”9

Goodrich’s labor of love and prayer came to an end in 1860. There is no conspicuous memorial to him at Yale, and this is understandable, for his work was pervasive but quiet, and the man himself unassuming. But his gravestone in Grove Street Cemetery says it well:

“Not slothful in business,

Fervent in Spirit,

Serving the Lord.” (Romans 12, KJV)

Marena Fisher, Graduate ’92

© 1999 The Yale Standard Committee

1. Theodore Dwight Woolsey, “A discourse commemorative of the life and services of the Rev. Chauncey Allen Goodrich,” New Haven, 1860.

2. Goodrich Family Papers, MS 242, SML Mss. & Archives, April 9, 1809.

3. August 23, 1815, MS 242.

4. 1816, MS 242.

5. October 1845, MS 242.

6. Woolsey, 1860.

7. Franklin B. Dexter, “A selection from the Miscellaneous Historical Papers…”, New Haven, 1918.

8. July 5, 1846, MS 242.

9. Revival lectures, MS 242.

Noah Webster, In His Own Words |

Most people today know New Haven’s Noah Webster (Yale, 1778) as the author of a great dictionary, but few know much about Webster the man. Converted at age fifty through the bold evangelism of Moses Stuart (Yale, 1799), the eminent lexicographer never tried to seal his day-to-day work off from his faith (see definition for Happy below.)

Looking back on his life as a skeptic he said:

“… I had for almost fifty years exercised my talents such as they are, to obtain knowledge and to abide by its dictates, but without arriving at the truth, or what now appears to me to be the truth of the Gospel. I am taught now the utter insufficiency of our own powers to effect a change of heart, and am persuaded that a reliance on our own talents and powers, is a fatal error, springing from natural pride and opposition to God.…” (E.E. Fowler Ford, “Notes on the Life of Noah Webster,” New York, 1912, vol. 2, pp. 44-46.)

HAP’PY, a. [from hap; W. hapus, properly lucky, fortunate, receiving good from something that falls or comes to one unexpectedly, or by an event that is not within control. See HOUR.]

1. Lucky ; fortunate ; successful.

Chemists have been more happy in finding experiments than the causes of them. Boyle.

So we say, a happy thought; a happy expedient.

2. Being in the enjoyment of agreeable sensations from the possession of good ; enjoying pleasure from the gratification of appetites of desires. The pleasurable sensations derived from the gratification of sensual appetites render a person temporarily happy; but he only can be esteemed really and permanently happy, who enjoys peace of mind in the favor of God. To be in any degree happy, we must be free from pain both of body and of mind; to be very happy, we must be in the enjoyment of lively sensations of pleasure, either of body or mind.

Happy am I, for the daughters will call me blessed. —Gen. xxx.

He found himself happiest in communicating happiness to others. Wirt.

(Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language, 1840.)