Living With All His Might: Jonathan Edwards and the Great Awakening |

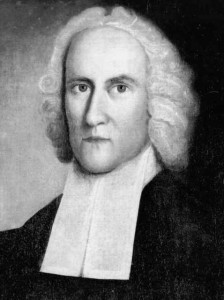

Despite the oft-depicted caricature of a scowling preacher who conjured up hell’s flames when he preached, Jonathan Edwards was a gentle man who through a lifelong labor of pastoral service quietly established himself as a towering giant in Christian history and Christian thought.

There were preachers of his day more dynamic than he, and missionaries more daring, but through a life of undeterred prayer and study, this soft-spoken preacher and scholar drew, persuaded, and inspired a generation of men and women into a vital relationship with Jesus Christ. And indeed, his influence continues. As the late great preacher Dr. Martin Lloyd-Jones wrote in 1976, “No man is more relevant to the present condition of Christianity than Jonathan Edwards.”

Edwards was born on October 5, 1703, to Timothy and Esther Edwards in a small town in the Connecticut river valley called East Windsor. He was the fifth child and only son among what would become eleven children. Timothy, a Harvard graduate, was minister to the town of about 300 inhabitants. Jonathan’s mother was of the eminent Stoddard family who held among them various important civic and ministerial positions in Massachusetts. It was in his childhood, bathed in the beauty of the valley, that a fondness for nature was instilled—an admiration which would later be expressed in a much-praised academic paper on spiders.

Two years before his birth, down the Connecticut River, Yale College was born (not yet named as such nor yet established in New Haven) as a response to the growing intellectual infidelity of Harvard. Taking seriously God’s command to Moses “you shall not add to the word I give you nor take from it,” Puritan ministers turned their hopes to this new institution as a haven for unadulterated Biblical teaching.

The new school’s founding proved to be a critical fact in Edwards’s life for he would enter the college thirteen years later a freshman.

At Yale, Jonathan quickly showed himself a gifted student. In his senior year, he was given the unusual honor of being appointed the college butler while still an undergraduate. At graduation, as the highest ranking student of his class, he was called on to deliver the farewell address.

One principal concern had increased in Jonathan’s mind by the time he was a senior: his desire to know God. Putting academic books aside one day, he picked up his Bible as he had done many times before. But this time the words made an impact as never before. He wrote of the experience:

“The first instance that I remember of that inward, sweet delight in God and divine things was on reading those words ‘Now unto the King eternal, immortal, invisible, the only wise God, be honour and glory for ever and ever, Amen.’ As I read there came into my soul a sense of the glory of the Divine Being.”

Jonathan Edwards would leave Yale having gained not just an education but a vibrant relationship with Jesus Christ—just that balance of collegiate benefits the founders of the school had envisioned and prayed for. It was after his conversion that he made his promise to God and himself: “Resolved, To live with all my might while I do live.” After graduation, Edwards spent several years first as pastor of a small Presbyterian parish in New York City, then as a tutor at Yale where he was able to continue his studies in philosophy, the natural sciences (he wrote his paper on spiders then) and theology. Yet growing increasingly unsatisfied with purely academic endeavors, and desiring to occupy himself with concerns more directly touching the spiritual welfare of people, he sought God for a break into a new situation.

The break came in the fall of 1726 when the church in Northampton (also in the Connecticut river valley in central Massachusetts, where his highly-regarded yet aging grandfather Solomon Stoddard was preaching) invited him to take up residence as assistant pastor. Northampton would be his home for the next 23 years, and the place with which his name would be indelibly connected.

Stoddard had ably led the people of Northampton, who by then consisted of about 200 families, for the past 56 years, having overseen five special spiritual awakenings in the town. Of these times, Edwards recalled, “I have heard my grandfather say, the greater part of the young people seemed to be mainly concerned for their eternal salvation.” Unbeknownst to Jonathan as yet, history would prove that these special occasions had only been primers for what would come under his own pastorate.

Before telling the story of the Northampton revival, it should be mentioned that less than a year after his arrival, Edwards married Sarah Pierpont, whom he probably first spied in a meetinghouse when he was a tutor at Yale. Though she was only thirteen when he first saw her, he noted her as “a rare example of early piety.” Four years later, they were married, and would continue in their loving bond for thirty years until Edwards’ death. As one early biographer wrote, “Perhaps no event of Mr. Edwards’ life had a more close connection with his subsequent comfort and usefulness than this marriage.”

It was in the winter of 1734 that, as Edwards narrates, “the Spirit of God began extraordinarily to set in, and wonderfully to work amongst us: and there were, very suddenly, one after another, five or six persons, who were to all appearances savingly converted.” With that opening salvo from God, a widespread concern among people for their own spiritual condition swept through Northampton. Similar events had been transpiring in towns throughout the river valley and other parts of Massachusetts and Connecticut.

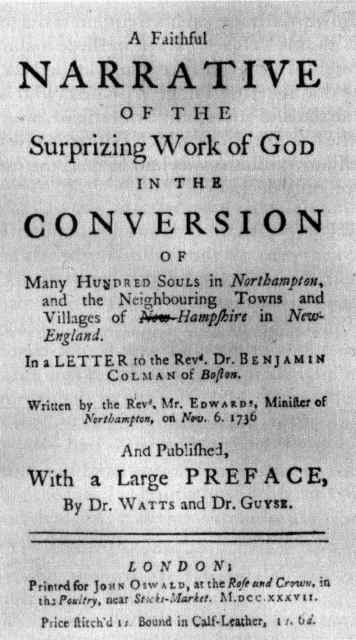

The effect was immediate and deep. In his Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God, Edwards writes, “When once the Spirit of God began to be so wonderfully poured out in a general way through the town, people had soon done with their old quarrels, backbitings, and intermeddling with other men’s matters. The tavern was soon left empty and persons kept very much at home.”

Further, “our public assemblies were then beautiful: the congregation was alive in God’s service, everyone earnestly intent on the public worship . . . the assembly in general were, from time to time, in tears while the Word was preached: some weeping with sorrow and distress, others with joy and love.”

While pressing home the consequences of sin, and shrinking in no way from the Scriptural fact of hell, Edwards and other preachers held out Jesus’ salvation through faith alone. As people wrestled with their eternal condition, they found relief in Christ. Edwards wrote, “The town seemed to be full of the presence of God; it never was so full of love, nor joy, and yet so full of distress, as it was then.”

Within six years, this spiritual fire would catch throughout all the colonies and also across the Atlantic through the preaching of George Whitefield and John Wesley. Northampton in 1734 was lapping at the heels of a period that historians would later call “The Great Awakening” for the generality and intensity of people’s concern for their eternal salvation.

Edwards’ Faithful Narrative played a critical role in informing a largely ignorant wider public, both in the Colonies and in England, of what was happening in Northampton. The account helped inspire a new crop of English revivalists, notably Wesley, towards effecting similar spiritual blessings in England.

By 1742, however, the revival had dissipated into, as one eyewitness wrote, “strife and faction,” in large part because of the emotional excesses that had crept into congregations. Edwards recognized the danger of substituting for the true conversion experience mere “wildfire” and “enthusiasm,” and labored to keep such “irregularities” to a minimum. While recognizing the profundity of God’s work in a life, he maintained the need to keep a steady state of mind.

While enemies of the Awakening seized the excesses to condemn the whole of what happened, Edwards kept a measured assessment. He wrote, “there may be some mixtures of natural affection . . . some imprudences and irregularities, as there always was, and always will be in this imperfect state, yet as to the work in general . . . they have all the clear and incontestable evidences of a true divine work.”

In May of 1747, Edwards met a young veteran missionary whose extraordinary work among the American Indians he had been reading about. Although by this time David Brainerd was nearly overcome by tuberculosis, his acquaintance with Edwards in the remaining five months of his life proved to be significant, if for no other reason than that it would lead to a biography that would energize a slumbering missionary movement both in the Colonies and abroad.

Converted at the height of the Great Awakening while a student at Yale, Brainerd was the unfortunate object of the ire of the college government after he criticized the spiritual quality of one of his tutors. Though at the top of his class, and despite his submission of an apology, he was denied his degree. (This widely perceived injustice became a significant motivation for the formation of Princeton College.)

Without a degree, yet full of faith in God, he interviewed with members of the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, who determined he was the man of their choice to bring the Gospel to the American Indians.

Working among the Kaunaumeek and Delaware Indians in New Jersey, Brainerd persisted for years with no visible result from his preaching. But in the summer of 1745, when he was physically worn and discouraged to the point of quitting, an awakening came among the New Jersey Indians that was, as one historian put it, “one of the most remarkable in Christian history.”

Deeply moved by Brainerd’s death, Edwards felt it his duty to put his story on paper. The biography soon gained an international following and was the first American-printed biography to do so. Over the next hundred years it would do more to raise Christian consciousness about missionary work than any book of its era.

A New England minister who had an especially difficult parish to shepherd told about the help he derived from The Life and Diary of the Rev. David Brainerd in these terms: “and when we shut the book we are not praising Brainerd, but condemning ourselves, and resolving that, by the grace of God, we will follow Christ more closely in the future.”

Edwards’ contact with Brainerd would prove to be of more than personal interest, but preparatory for his own missionary work among the Indians of Stockbridge, Massachusetts just a few years later.

His move to Stockbridge in 1751 was, in fact, the result of a sad conclusion to a doctrinal controversy in his parish. His grandfather had established the practice of allowing those who were not professedly Christians to take part in the church communion. After careful study of Scripture and much prayer, Edwards found himself unable to accept this practice as Biblical, and proceeded to limit the communion table to only those who were expressly converted.

This overturning of tradition caused a great stir in the town, and particular leading families who had harbored other resentments against Edwards seized the opportunity to try and dismiss him as their pastor. Remaining calm and steady through the whole affair, Edwards reasoned with the people, but to no final effect.

By a majority vote of the ruling council, Edwards’ relationship with the Northampton parish was dissolved. It was then that Edwards answered a pastoral call from an outpost town in western Massachusetts called Stockbridge. There he preached to the white settlers and the Housatonic Indians, as well as set up schooling for both white and Indian children. Whatever time he had left he put into his writings. In this way, Edwards spent the last years of his life.

In 1755, the trustees of the recently established College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) called upon Jonathan Edwards to take over the presidency. Hesitating at first, he eventually acceded to their pleas. However, illness would intervene at the outset of his term as president. In 1758, after receiving a smallpox vaccination that was too strong, he died at the age of 54, having lived a full life of service to God.

Leaving a legacy of service, and writings that would become classics in Christian literature, Edwards plainly fulfilled his old college resolution to “live with all my might.” One other resolution he formed back at Yale was, “Resolved, To strive every week to be brought higher in religion, and to a higher exercise of grace, than I was the week before.” So he did, from day to day and week to week, for the sake of his Savior, and blessed us all.

Steve Ahn, JE ‘96

© 2000 The Yale Standard Committee