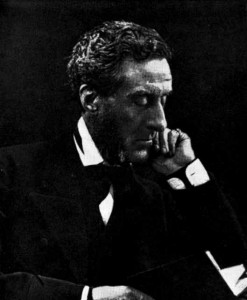

Lord Shaftesbury: God’s Reformer Lord Shaftesbury (1801-1885) |

The room was large, but filling up rapidly. In it were nearly four hundred thieves of every description, from elegant dandies in black coats and white neckcloths, to scarred, fierce-looking toughs without shirts and stockings. Several of the most notorious and experienced stood by the door to deny entrance to any who were not professional criminals. Only two law-abiding citizens were admitted: Thomas Jackson, a London city missionary, and Lord Ashley, heir to the Earldom of Shaftesbury.

The thieves knelt quietly while Ashley opened the meeting in prayer, and then it was the noble lord’s turn to listen as the thieves gave “graphic and picturesque” accounts of their lives of crime. Ashley promised to help them emigrate, to begin their lives afresh in scenes where none would know their former occupations. One thief, though, on behalf of the rest, asked Lord Ashley, “But will you ever come back to see us again?” “Yes,” replied Ashley, “at any time, and at any place, whenever you shall send for me.”

Many of Lord Ashley’s upper-class acquaintance disapproved of his work with the criminal and the destitute, but Ashley himself said, “I feel my business lies in the gutter, and I have not the least intention to get out of it.” The story of how a British peer came to give his life to “those who had none to help them” is worth telling.

The famous men of Ashley’s family had not been particularly self-sacrificing. The first Earl was a ruthless statesman who became Dryden’s picture of evil genius in the poem “Absalom and Achitophel.” The third Earl was a noteworthy apologist for Deism. Ashley’s father, the sixth Earl, was an egotist, commendably efficient as a chairman of committees in the House of Lords, but a brutal tyrant to his children. In childhood, Ashley preferred the “tender mercies” of the servants, who let him go to bed cold and hungry, to those of his parents, who bullied him constantly, verbally and physically.

The one person who treated him well was Anna Milles, the family housekeeper. She loved him and told him Bible stories, and taught him to pray. “She told him of Calvary and the Empty Tomb and spoke of the Lord Jesus as the risen Redeemer who could be a Friend.” (Pollock 20) Ashley believed because of her witness and later said, “God be praised for her and her loving faithfulness; we shall meet… in the House where there are many mansions.” Ashley’s choice for Christ became the determining fact of his life.

As a young man, Ashley was uncertain of his abilities, and not at all sure what his life’s work should be. Even after he was elected to Parliament for the first time in 1826, he remained unconvinced that he had the gifts of a statesman.

But Ashley’s personal misgivings about his talents began to subside in his thoughts when he served on the House Select Committee on Lunacy. The treatment routinely given the insane in early nineteenth- century England beggars belief today. Strait-jackets, chains, and whips were all in common use, and cures were not usually attempted. The cruelties Ashley heard of sent him to the asylums to see for himself.

He tried to make his visits on Sunday because the keepers were out at that time and left their patients to “pain and filthiness,” chained with only food and water in reach. Ashley noted there was “nothing poetical” in visiting cells of misery where the “stomach rebelled,” but his efforts led to the passage of new laws regulating the asylums. He helped lay the foundation in England for the humane treatment of the insane, which we take for granted today.

Rescued Children

Ashley became alive to the sufferings of the weak and friendless, and began to act upon what he saw. Looking out a window at the back of his house one morning, he noticed a little boy carrying a heavy load of brushes and rods upon his back. The boy was covered with soot and his limbs were distorted. A man walked beside him, beating him as they went; it was a chimney sweep and his apprentice.

Ashley investigated the trade and discovered the miseries to which the sweep’s boys were subjected. Their bodies were rubbed down with salt water before a hot fire to harden the skin, and they were sent naked up narrow chimneys to clean out the soot. If a boy got stuck in a chimney, the sweep would start a fire to encourage him to struggle till he got free. Some boys suffocated, many got cancer, and nearly all grew up physically deformed. Some sweep’s boys were in fact girls.

Though chimney-cleaning machines had been invented, most property owners would not pay money to have their chimneys straightened so as to accommodate machines. Sweeps kept their boys out of sight as much as possible to keep others from noticing their misery and raising a public complaint. Many before Ashley had fought to stop the use of climbing boys, and thirty-five years of effort would pass before he saw the practice abolished.

Though discouraged and puzzled by his continual failure over many years to free the boys, Ashley (now Shaftesbury) said, “I must persevere, for however dark the view… I see no Scripture reason for desisting; and the issue of every toil is in the hands of the Almighty.” Later, many were grateful for his persistence. John Pollock notes:

“Long after Shaftesbury was dead a speaker at a public meeting was astonished at exceptional applause produced by a casual mention of the name. He asked what they knew of him. A man arose and shouted, ‘Know of him? Why, I’m a chimbley sweep, and what did he do for me? Didn’t he pass the Bill? When I was a little ‘un I had to go up chimbleys, and many a time I’ve come down with bleedin’ feet and knees and a ‘most choking. And he passed the Bill and saved us from all that. That’s what I know, Sir, of Lord Shaftesbury.’”

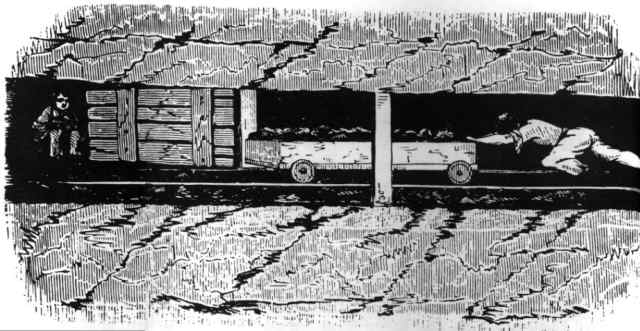

Tenacity was key to many of Shaftesbury’s battles, including his fight to change working conditions in the coal mines. In 1840 he secured the appointment of a Royal Commission to investigate the working conditions of children. The commissioners visited the coal mines first, and their findings were so shocking that the Home Office tried to suppress their report. The work hours even for children in the mines were 12 to 14 a day. Children and women worked alongside men crawling and toiling along narrow shafts and up endless stairs carrying enormous weights of coal. Women stayed at this work “until the last hour of pregnancy.” Along passages of the mine not more than 18 to 24 inches in height, boys and girls moved carts of coal, pulling them like beasts of burden.

Children working in a mine

Because of the heat and dirt, most of the miners did their work naked, and even the women and children wore little clothing. Sexual and physical abuse were part of life in the mines.

The public reaction to the Commission’s discoveries was enormous, and Ashley constructed a Colliery bill to free women and children from the mines. The sitting administration (made up of his own party) opposed him, and many delays ensued before he was allowed to read the bill in Parliament. But Ashley found that though men deserted him, God would not. He later reported that as he rose to deliver the bill before the House of Commons, “The words of God came forcibly to my mind ‘Only be strong and of a good courage’—praised be His Holy name I was as easy from that moment as though I had been sitting in an armchair.”

For two hours he unfolded the horror of the mines before a hushed chamber. Some members wept, and Ashley closed to cheering and a roar of applause. The social activist Richard Cobden, who had opposed Ashley’s reforms in the past and sneered at him as an “aristocratic and canting simpleton,” came over to shake his hand. He said, “You know how opposed I have been to your views. But I don’t think I have ever been put into such a frame of mind in the whole course of my life, as I have been by your speech.” The bill passed and the “slavery” of women and children in the mines was abolished.

Other parts of Shaftesbury’s life show he was no mere social reformer, but a man actively seeking every opportunity to serve the Lord. He dealt not just in the spiritual needs of his own generation, but came to understand and support God’s plans for the generations to come. In the 1830’s, Bible prophecies studied with Hebrew scholar Alexander McCaul and others convinced Ashley and his wife that God purposed to restore the Jews to the Holy Land, and that the time was near. At an opportune time he proposed to Prime Minister Palmerston that a Jewish national home be created in Palestine under British protection.

Though Britain soon established an official presence in Palestine, Ashley’s efforts for the restoration of the Jews came to nothing at this time. But he never abandoned his hope. To the end of his life he wore a ring sent to him by a Jewish believer in Jesus, which was inscribed, “Oh, pray for the peace of Jerusalem; they shall prosper that love thee” (Psalm 122). In 1876, three quarters of a century before the rebirth of Israel, he said of the Jewish restoration, “A nation must have a country. The old land, the old people. This is not an artificial experiment, it is nature, it is history.”

When the American evangelist D. L. Moody came to England in 1875, Shaftesbury quickly concluded that Moody looked “amazingly like the right man [to evangelize the nation] at the right hour.” Moody, an unpretentious man, was anxious to reach the working classes but afraid to address himself to the “higher” classes. Shaftesbury urged him to preach to the working poor in the East End of London, but also to hold evening meetings in the West End where those of high intellectual and social position congregated.

It turned out that the West End meetings were, if anything, more heavily attended than those in the East. The Haymarket theater area was “literally blocked with the carriages of the aristocratic and plutocratic” coming to hear Moody.

One of those converted in the West End meetings was Edward Studd, a retired plantation owner from India. His son C. T. Studd became a Christian through his father’s influence. Along with six other men from Cambridge University he abandoned wealth and athletic fame to become a missionary in China. The choice of these “Cambridge Seven” profoundly influenced college students of their generation.

This article is at best a sampling of Shaftesbury’s life and work. He is perhaps most commonly associated with the Ragged School movement, which educated generations of Britain’s orphaned and abandoned children. Many of these children became influential citizens in their own right, in England and abroad. Shaftesbury’s program for thieves’ emigration has already been mentioned. Within one year of his meeting with the thieves, three hundred of them had found employment in England and abroad. Some abandoned their lives of crime on the basis of the meeting alone.

Shaftesbury’s advice on how to live the Christian life is worth drawing on today:

“Christianity is not a state of opinion and speculation. Christianity is essentially practical…. No [one], depend upon it, can persist from the beginning of his life to the end of it in a course of self-denial… in a course of virtue… in a course of prayer… unless he is drawing from the fountain of our Lord Himself. Therefore, I say to you again… let your Christianity be practical.”

Marena Fisher, Graduate ‘92

© 1997 The Yale Standard Committee

Quotations for “Lord Shaftesbury: God’s Reformer” taken from John Pollock’s Shaftesbury: The Poor Man’s Earl, 1985. Edwin Hodder’s The Life and Work of the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, 1886. G. F. A. Best’s Shaftesbury, 1964. Barbara W. Tuchman’s Bible and Sword, 1956.