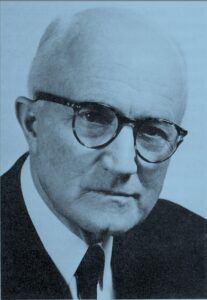

A century from now, scholars may find themselves asking how many prodigies there were back in the twentieth century named Kenneth Latourette. It will certainly appear that no one man could have left behind the brilliant record of accomplishment to which that name is attached. Dr. Kenneth Scott Latourette was a world-renowned historian, the author of 83 books (each a product of exacting scholarship), holder of seventeen honorary degrees, an authority of the first rank in the study of the Far East, former president of the American Historical Association—let the list be cut off here. It is less than half of the whole, but it is enough.

Yet the most extraordinary thing about this extraordinary man was the way he befriended his students on an intensely personal level, hundreds of them. Many remained in the circle of his friendship for the rest of their lives. As an undergraduate I was one of those who came to know him by that name by which he loved to be addressed by students, Uncle Ken. The day I met him, as a freshman, he wrote my name into a small notebook he carried. He did that, I later learned, so he would not forget to pray for me daily, as he did for many students, former students and acquaintances scattered over the world.

In the days when the conflicting claims of scholarship and individual problems of the students compete for a professor’s time and attention, the example of Dr. Latourette, who was Sterling Professor of Missions and Oriental History, deserves special attention. His death in December at the age of eighty-four meant an acute personal loss for the many who knew and loved him and the end of an era for Yale with which he had been so closely connected since coming as an undergraduate in 1905.

His death in December at the age of eighty-four meant an acute personal loss for the many who knew and loved him and the end of an era for Yale with which he had been so closely connected since coming as an undergraduate in 1905.

A man of extraordinary vitality and strength to the very end of his life, he was a familiar figure at the Divinity School where he lived and had three groups of students who met weekly at his fireside for discussion and at Berkeley College where he welcomed undergraduates in his office Monday evenings. Since he had been Emeritus for many years, however, most undergraduates knew little about this amazing scholar and friend.

It would be impossible even to list in this brief article the definitive and ground-breaking books that he wrote on the Far East. A recent article in the “China Notes” calls him “the man who has done more than any other in the twentieth century to inform the western world about China in general and the Christian factor in particular… No other scholar has exerted so great an influence on the educational awakening of the American people, of all English speaking peoples, to the life-experience of China.”

Starting soon after his return from China, where he had gone as a missionary, and his recovery from the illness that had necessitated that return, he began a systematic presentation of China to a world that knew almost nothing about it. In his own words, “when I began teaching Far Eastern history, I could count such teachers in American universities on the fingers of my two hands and have some fingers left over.” With The Development of China (1917) and The Development of Japan (1918), he began a shelf full of books on that area that long remained standard and in use as textbooks, continuing right down to China (1964), including The American Record in the Far East, 1945-1951 (1952); A Short History of the Far East (665 pages, 1946). At his insistence, the title of this professorship put Missions first, as he was throughout his life first a missionary and secondly a teacher. In this area his work is monumental. The article quoted above states, “No person in this century, indeed in any century, has done so much in study and presentation of the missionary record of the Christian people.” The scope and boldness with which he opened an area of study which before him had been confined to the limited viewpoints of denominational prejudice is demonstrated by his major achievements:

- A History of Christian Missions in China, 1929.

- History of the Expansion of Christianity, 7 volumes, 1937-45.

- A History of Christianity, 1953, (1516 pages)

- Christianity in a Revolutionary Age, 5 volumes, 1958-62.

He also wrote The Gospel, the Church and the World (1946), These Sought a Country (1950), and Master of the Waking World (1958), among his more-than-eighty books. Over a million copies of his books have been sold (they cannot be considered light reading) – to say nothing of the shorter studies, articles, encyclopedia pieces and some 750 book reviews! It is therefore not surprising that he was honored with six different types of honorary degrees from five different countries (more than any other Yale professor): a total of 17.

What is nearly unbelievable against this background (which omits, even at that, any mention a of his teaching load and service on numerous boards and committees), is the quality of his personal life and the time and concern he devoted to students. I well remember the Monday night when, as a freshman, knowing nothing about “Uncle Ken,” (as he asked us to call him) I was introduced to him in his office in Berkeley. The vigor and enthusiastic understanding with which he answered our varied questions about Yale, China and church history gave little evidence that he was nearing eighty, nor did his clear, kindly face and his habit of walking the long trip down and back to the Divinity School at least once a day. he was so fresh in his outlook that few who talked with him realized that his life stretched back to include nearly the entire history of Yale in this century. A persuasive spokesman for the standards on which Yale was founded and through which it became great, he enjoyed telling stores of the Yale men who stood out for God in their generation.

When personal problems came up or students wanted to talk of the question of life work, Uncle Ken gave willingly of his time and, drawing on his wealth of experience, patiently counseled and was instrumental in more than one young man’s finding his course in life. In recent years, he not only dissuaded one student on the verge of suicide from that extremity, but started him on the road to a living faith in Jesus Christ.

Years after I first met him I learned why he wrote down the name of the students he met: he told me that since the day he had first met me he had prayed for me daily. He believed that prayer for other people was one of the chief tasks of a Christian and it was his delight to tell students of the hard-won convictions that had stood the test of his many years and gave him such peace and joy as he looked forward to eternity. He loved to quote Noah Webster’s dying words, “It’s been wonderful to live with Christ here—how much better hereafter!”

The article that follows tells briefly of his life and of the Yale which shaped it and which he loved so thoroughly.

Calvin B. Burrows, Class of ‘66

Excerpts from Beyond the Ranges

By Kenneth Scott Latourette

Kenneth Scott Latourette was born in Oregon City, Oregon, on August 9, 1884. Excerpts from his 1967 autobiography, Beyond the Ranges, follow:

“In September, 1905, I arrived in New Haven, knowing almost nothing more about Yale than its name…. Yale itself had a warm Evangelical tradition which extended well back into the eighteenth century… In the fore part of the nineteenth century the religious life had again and again been quickened by awakenings. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century (Dwight L.) Moody and (Henry) Drummond had had a profound effect on the student body. At the student summer conferences at Northfield which were led by Moody and after the latter’s death by John R. Mott, in the Moody tradition, Yale long had the largest delegation…in 1901, only four years before I came to Yale, a few of the recent graduates who were planning to be missionaries organized what became the Yale Foreign Missionary Society through which Yale men, supported by Yale friends, began as a group a mission in China. In common with several Eastern colleges, attendance was required at daily and Sunday chapel services. During my student years no complaint was raised against the custom. Indeed, my class voted overwhelmingly for its continuation. Immediately after Sunday chapel each of the four classes had a prayer meeting in Dwight Hall, led by members of the class… In Dwight Hall was also the ‘Semi-circular Room,’ where small groups met for prayer and where what was known as ‘the Student Volunteer Band,’ composed of those who were headed for foreign missions, met, usually weekly. Each Wednesday evening classes for Bible study gathered, one for each of the four classes…

“One member of the class especially interested me. He was a warm-hearted Irishman with whom I shared a table in Commons and one of my classes. Before I arrived he had become notorious for his flouting of most of the moral conventions. He drank heavily, had irregular relations with women, and most of the class, disgusted, had written him off. Because of poor grades he failed to graduate and his father disowned him. Toward the end of the year I asked him why he did not stop his headlong course, saying that he knew as well as I what it would lead to. To my surprised he said that he would. Then, at my suggestion, he gave me his hand on it. Somewhat to the embarrassment of us both I told him that I would remember him in prayer. At our triennial reunion he came and attached himself to me, for he knew that in my company he would do no drinking He later married a girl who knew all about him, but loved him and believed in him. He died early, probably as a result of his college dissipation.

“One friendship in my senior year, which had as great an effect on me as any formed at Yale, was with Henry Burt Wright, of the class of 1898. Henry Wright was the son of the Dean of Yale College…while an undergraduate he made a conscious and revolutionary commitment at a Northfield Conference as a result of an appeal by Moody for a decision for Christ.

“…After taking his Ph.D…he became a member of the faculty of Yale College. His chief concern was for individuals. He taught a freshman Bible class in the life of Christ, for to him Christ was central. He won many a man to Christ, some of them students, some adults, others rough lads in Oakham, the Massachusetts village where his father had been reared and where the family spent its summers. He was the most indefatigable personal evangelist I have ever known. He gathered about him a group, mostly of students, who shared his commitment to Christ, which met weekly and with whom he revealed his deepest purposes and his faith… It was chiefly that experience which has led me throughout my teaching years to gather similar groups. When, in my emeritus years, I was relieved of teaching and administration…I multiplied the groups until they numbered four—three meeting weekly by my fireside in the Divinity School and one in my office in Berkeley College, where I have been a Fellow.”

“In my final year I was made Bible study secretary of Dwight Hall to supervise the entire structure. That year we had about 1,000 undergraduates enrolled in the groups. At the same time Henry Wright had his freshman class in the life of Christ, with an average attendance of about 100. I attempted to know every man in the classes of 1909, 1910 and 1911… Possessed by the compulsive conviction, which had driven me to prepare for foreign missions, I believed that every Christian student should show reason why he should not become a missionary. I therefore approached many undergraduates with that appeal… From the class of 1909, which I knew throughout its four years, with possibly one exception, came more missionaries than from any other class in the history of Yale College. That exception was Class of 1892. In actual years of service as missionaries 1909 surpassed all other classes except 1892.

“A potent influence in 1909 was William Whiting Borden. He was from a wealthy Chicago family… Bill had made a full commitment to Christ. He entered Yale purposing to be a missionary. He planned to go to a real frontier, the Moslems in West China, and to seek appointment under the China Inland Mission. He was an able student, president of Phi Beta Kappa in his senior year. He was athletic, of great energy, handsome, and a born leader of men. He could have excelled in business or in almost any profession… After Yale he entered Princeton Theological seminary and graduated. Then he went to Egypt to study Arabic, planning to go from there to China for the Chinese language. While in Cairo he was taken with spinal meningitis and died (1912). His biography, Borden of Yale, ’09… has had a profound influence on successive generations of students. I look back on his friendship as one of the richest I have known.

“The Missionary Years”

“At the end of the Northfield Conference of 1910 I went to China by way of Europe. Since most of my family were on the West Coast, the only relative to see me off was a cousin of my mother who lived in Brooklyn… Characteristically, Henry Wright made a special trip from his summer retreat in Oakham to bid me bon voyage. In our evening devotions he gave me a verse which he suggested that I take as guide: ‘I can do all things through Christ, who strengthens me.’”

“…I took a train to Moscow to catch the Trans-Siberian express… At Kuling I was introduced to the missionaries of many denominations…

“Standing out vividly in my memory of those first days in Kuling was a brief conversation with Timothy Richard, Welsh Baptists, then in late middle life. Erect, with ivory hair, ruddy face, and flashing eyes, he would attract attention in any company. He had worked and dreamed in terms of all China—in personal evangelism, in fighting famine, and in seeking to aid the Chinese leaders as they sought to adjust to the invasion of the Occident… When I was introduced to him he asked my plans. Embarrassed, I stammered something about what Yale-in-China was attempting. I have never forgotten his kindly but challenging impatience. ‘In how large terms are you planning?’ he cried.

“…Toward the end of the summer I had an attack of amoebic dysentery which proved my undoing… I had never been in bed from illness for as much as a day. The treatment was drastic…permanent damage was done to the colon… In March I left for the United States… So confident was I of resuming my work in Changaha that I purchased a round-trip ticket on a Yangtze steamer. The revolution was in full swing.

“A slow Pacific steamer brought me to San Francisco…But the hoped-for recovery did not come…the bottom dropped out…I could not even do light reading for more than a few minutes at a time. Deep mental depression followed—fortunately with no thought of suicide.

“…By the summer of 1914 I was enough improved to undertake part-time regular teaching. [He taught for two years at Reed College in Oregon] …in retrospect I am convinced that had I remained I could not have made my largest contribution…a kind of self-conscious intellectual pride, especially in the department of the humanities, would to me have proved basically stultifying.” [He taught next at Denison College in Ohio.] “…my energies at Denison were chiefly directed toward students. …In several ways I formed friendships with undergraduates. During springs and autumns I played tennis with them. I dined…and hiked with them…To numbers of the men I presented foreign missions as a challenge. A few responded and gave outstanding service. Some I counseled in scholarship and aided in their initial attempts at writing. I came to know most of the students. [As he wrote books of history, offers came: to head a department of Far Eastern studies, to be president of a college, to occupy a new chair of mission of the University of Chicago, others.]

“What was God’s will? Where could I best serve His purposes? My reason for [accepting] the Yale post were several. I could resume my connections with Dwight Hall and Yale undergraduates. More important, I could fulfill my missionary purpose by helping to prepare missionaries, by presenting missions as a life work to undergraduates, by acquainting future pastors with foreign missions, by serving on boards and committees in New York which had to do with the world mission, and by writing. The Day Missions Library…offered unexcelled facilities for research in missions… I went to the Yale faculty from sheer sense of duty. I am now certain that I was seeing dimly, but decisively, the divine purpose for my life.

Many years were to pass before this became clear. As will appear in a later chapter, my first decade at Yale, as were my months in China, was troubled and frustrating. But from the perspective of old age I am certain that what looked like sacrifice was the door to the fullest use of the capacities with which God had endowed me and, in these later days, to an unbelievably rich and quietly happy life.

“Almost immediately after my arrival, in September, 1921, doors began to open. In addition to my office in the building of the Day Missions Library, I chose to take rooms in the Divinity School, and had a suite of three… The study, with its fireplace, quickly became the meeting place of a weekly informal group of students on the floor… I was elected to the trustees of Yale-in-China and early became chairman of its personnel committee, a post I was to occupy for about forty years.

“…death came to Henry Wright. He was a in Oakham for the Christmas recess and had a hemorrhage in a lung that had earlier been badly damaged through an infection contracted several years earlier while he was nursing one of the lads of that village who was dying of tuberculosis. His last words were: ‘Life here with Christ has been wonderful; it will be richer hereafter.’

“In New Haven I continued my contacts with Dwight Hall and came to know some of the leaders… The temper had changed almost beyond all recognition… The kind of Bible study, indeed any voluntary bible study such as had flourished before World War I, was impossible. Very few undergraduates would listen to a suggestion that they consider foreign missions or even the ministry as a life work. Undergraduate agitation against required chapel was vocal and shortly prevailed.

“…A combination of causes brought me to an extreme physical and emotional crisis…boards and committees on which I held membership took a heavier toll than I had realized. In addition, and more of a drain, were basic questions of the faith. I had come to see something of the seamy side of ecclesiastical and official religious life… Among presumably sincere Christians I found self-seeking for position and prestige, often rationalized as orthodoxy of liberalism… On my mother’s side of the family some, including the most brilliant intellectually and the best read in such subjects, had taken a reverent but agnostic attitude toward religion…I was aware of it and never had been forced to come to grips with it…

“During that autumn I reached a nadir, but also had the beginning of the answer. Again and again I had climbed mountains in the Pacific Northwest. As I grew older I would lie in my sleeping bag under the stars, bright and glittering in the thin air, and would wonder whether there was anyone in that vast universe who cared for me and my fellow human beings any more than I cared for the ant which I crushed when it was trying to crawl in with me for shelter.

“As through all the years, students remained my chief interest… I came to know well many undergraduates in my classes.”

“A Crises of Faith”

“For weeks in that autumn of 1925 I realized that I was at last an agnostic and perhaps an atheist. If that attitude persisted, I would, in all honesty, have had to resign from the faculty of the Divinity School and the ministry. I can still remember almost the precise spot in a street in Portland when, like an illumination, the beginning of the answer flashed on me. ‘Here,’ I said, or a voice seemed to say to me, ‘is my father. He has never let me down and has always been dependable. Unless there is Some One in the universe who is at least as dependable and as intelligent as he, by whatever means he has been brought into being, the universe does not make sense. All our science is based on the conviction that we live in a universe, not chaos.’

“…At the time, with my historical training and the questions raised by specialists in the New Testament, I was far from certain that we could know much about Jesus. However, as time passed and I continued to listen to my colleagues, to read their books and the books by other specialists, I ceased to wonder whether knowledge of their fields would make the Christian faith untenable… I found—or was found by—sufficient faith to remain on the faculty of the Divinity School.

“For weeks in that autumn of 1925 I realized that I was at last an agnostic and perhaps an atheist. If that attitude persisted, I would, in all honesty, have had to resign from the faculty of the Divinity School and the ministry.”

“Not immediately, but as the months and years passed, increasingly, from experience and thought based on extensive reading, I found the Evangelical faith in which I had been reared confirmed and deepened. Increasingly I rejoiced in the Gospel—the amazing Good News—that the Creator of what to us human beings is this bewildering and unimaginably vast universe, so loved the world that He gave His only Son, that whosoever believes in Him should not perish, but have everlasting life. Everlasting life, I came to see, is not just continued existence, but a growing knowledge—not merely intellectual but wondering through trust, love and fellowship—of Him who alone is truly God, and Jesus Christ whom He has sent. I was confirmed in my conviction that when all the best scholarship is taken into account we can know Christ as He was in the days of His flesh.

“Although I became familiar with the contemporary and recent studies of honest, competent scholars who questioned them, I was convinced that the historical evidence confirms the virgin birth and the bodily resurrection of Christ. Increasingly I believed that the nearest verbal approach that we human beings can come to the great mystery is to affirm that Christ is both fully man and fully God. Although now we see Him not, yet believing, we can ‘rejoice with joy unspeakable’ in what the Triune God has done and is doing through Him.”

“My chief interest continued to be students, undergraduates and those in the Divinity School… Students went with me on walks, short and long. I took many to dinner, some, especially freshmen, to Mory’s, where I became a life member (in prohibition days, when no liquor was served). For years I had a Bible class for freshmen in Dwight Hall…

“During the 1920’s Christian conviction and commitment among Yale undergraduates—and, I gather, in many other universities—dwindled. At its lowest point, near the end of the decade, the attitude of even most of the officers of Dwight Hall was that Christianity is interesting, if true. Concern for foreign missions was almost non-existent….Yet in the dreariest years some able undergraduates were unashamedly Christian. Several went into the ministry. A few prepared for foreign missions and in their maturity made outstanding contributions… Difficult though they were, the first ten years on the Yale faculty were extraordinarily rich in friendships and a questioned but deepening faith.

[On a visit to Palestine, Mr. Latourette found that, like the few undergraduates who were “unashamedly Christian” at Yale, there was a small remnant of believers among the Jews.]

“A limosine took me to Jerusalem, where for a few days I was the guest of Nelson Glueck in the American School. I arrived in a period of unusually acute tension between Arabs and Jews. Palestine was under British mandate, but violence might erupt at any moment. Curfew had been imposed. [He was particularly struck by Dr. Glueck’s] statement from his years of archeology in Palestine that of the hundreds of pre-Chrsitian Jewish graves which he had excavated all bore evidences of cults which competed with the worship of Jahweh—vivid evidence of the minuteness of the minority who held exclusively to the God who claimed their sole allegiance and by whom the writings of the prophets and the psalmists had been cherished and transmitted.

“Since my student years in Yale I had been concerned with the seemingly inevitable drift from their moorings of colleges and universities begun by earnest Christians and embodying the Christian faith. I sought to suggest possible ways of reversing the trend… Again and again in a variety of ways I attempted to obtain attention to the problem in more than one denomination, but with little if any success.”

“As through all the years, students remained my chief interest… I came to know well many undergraduates in my classes. [Many of these friendships with students lasted to the end of his life, or to the end of the students’ lives.]

“The Emeritus Years”

“…The privileges of the University were still accorded me, but my salary stopped and I was relieved of teaching and administration. I was serving on about thirty boards and committees in New York and New Haven, was seeing A History of Christianity through its proof stage, and had given three courses of lectures in other institutions, for which I was writing a small book… I had decided how to assign such years as remained…I had long decided not to accept appointments which would remove my residence from Yale…John Mackay twice asked me to head the Church History Department in Princeton Theological Seminary, of which he was president. [The offer tied in with] the global and ecumenical perspective which I was embodying in the seven-volume history of the Expansion of Christianity [but he turned it down to stay at Yale].

[He wrote]…a five volume history of Christianity in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries…I called it Christianity in a Revolutionary Age… The writing and publication of the five volumes were finished in 1963… [then] I turned my attention to projects which I had long been contemplating. One was a thorough revision of The Chinese: Their History and Culture… For some years I had been planning a short book which would cover in brief form, hopefully for popular consumption, the history of Christianity and distill my meditation on its place in the total record of mankind seen from the perspective of God’s purpose as recorded in the Scriptures. It appeared in January, 1965, as Christianity Through the Ages and as a paperback to facilitate its sale.

“Since it was a love of students which had been potent in bringing me into teaching, in my emeritus years, I made them, along with writing, my major concern. In the Divinity School three informal groups met weekly by my fireside… Any student was welcome… Other groups were cross sections of the student body. Usually I had not only a fire but apples… If a group asked it, and most of them did, I gave them communion twice or three times a year… To my joy I was called “Uncle Ken” by students and faculty… In these several ways the kind of friendship with students which I cherished was multiplied.

“The emeritus years passed quickly. They were the richest and happiest of my life. That was partly because of the congenial occupations, partly because of good health, but chiefly because of growing fellowship with God. Wondering and grateful appreciation of the Good News grew. More and more I was aware that God was beyond my full comprehension. Increasingly I came to see that the Trinity is the best description in human language of what underlies and infills the Universe—that the eternal God is Father, Son , and Holy Spirit. Each year I had fresh appreciation of the words of Paul—that now “abide faith, hope, and love, and the greatest of these is love.” To me the greatest is love because God is love, and herein is love, not that we loved God but that He loved us and sent His only Son to give us life. Because God is love, we can confidently have faith and hope, both inspired and given by that love. The Spirit Himself bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God, and if children, then heirs, heirs of God and joint hears with Jesus Christ.

“What lies beyond this present life I cannot know in detail, but I know Who is there and am convinced that through God’s grace, that love which I do not and cannot deserve, eternal life has begun here and now, and eternal life is to know God and Jesus Christ whom He has sent.

“…If, as an explorer, I have blazed trails into ‘the never, never country,’ if here and there have been lives who have seen, although dimly His Son in me, that has been through no merit of mine, but because by His initiative God sent His whisper to me.” (These are the closing words of the book.)

Reference: Beyond the Ranges. An autobiography by Kenneth Scott Latourette. Eerdmans, 1967.