Banner of Faith, Fountain of Service: The Original Dwight Hall |

A hundred years ago, Yale’s Old Campus looked a lot like it does today. What’s now Dwight Hall used to house the University Library. Connecticut Hall was there; Durfee and Farnham Halls lined two sides of the quadrangle. Wright Hall had not been built yet, but was preceded by Rose Alumni House. And adjacent to it, where the Giamatti bench now sits, stood a sturdy refuge of Victorian architecture with a broad corner veranda. Engraved in large capital letters above the portico was Matthew 23:10 in the original Greek: “One is your leader, the Christ.”

From the day it was dedicated, October 17, 1886, the original Dwight Hall building was a central meeting place—a home—for Yale students intent on transforming their campus, New Haven and beyond in the name of Jesus Christ.

Dwight Hall stirred with activity in the years from 1886 to around 1920. On Sunday evenings at Dwight Hall, anywhere from two hundred to five hundred men gathered to hear brief talks on Biblical teachings. There were also prayer meetings and committees for home missions and foreign missions. Students involved themselves with City Rescue Missions and Boys’ Clubs to help meet New Haven’s spiritual and social needs.

The Dwight Hall lecture course “brought eminent speakers to discuss religious questions of live interest.” Henry Drummond’s visit in 1887 was especially notable. Over 400 students attended each lecture; students and faculty alike were captivated by his frank, sincere, and reasoned presentation of Christian truths. He especially challenged those of high athletic, social, and intellectual prominence to use their influence to win men for Christ, and some of them became leaders in the Dwight Hall work.

At his suggestion deputations were sent out from Yale. Groups of students would travel to other colleges to strengthen ties with other Christian students, or they would visit preparatory schools to tell incoming freshmen about the opportunities for Christian service at Yale and about the vitality and earnestness of the work there. They particularly reached out to the Yale freshman class every opportunity to live “clean, consistent, and useful lives” from the outset of their college careers.

One reason for Dwight Hall’s influence was the tenor and quality of the men closely associated with it. Their lives of Christian service had honed their sense of purpose and built character in them that would serve them for the remainder of their lives.

Many students involved in Dwight Hall work later served as missionaries to foreign countries or actively promoted missions in the United States. For one, Horace Tracy Pitkin ‘92 was martyred in Pao-ting Fu in 1990 in China. It was largely because of his death that Yale students took an active interest in China. Eventually, the Yale-in-China mission was conceived and filled by a steady stream of students who founded schools, universities, and hospitals, much needed in the inland areas.

Sherwood Eddy ‘91, a missionary to India (and later to China and the United States), was equally well known as a personal evangelist and as a crusader for social justice. Professor Henry Burt Wright ‘98 willingly provided caring guidance and counsel to any student during his years at Yale from 1899 to 1923. “He created in generations of students a respect for moral reality, intellectual honesty, and complete consecration to the Christian cause.”

The original Dwight Hall did not spring up as an overnight surprise. Its roots reached well back into Yale’s origins and formative years. Yale was founded by 13 Congregational ministers in the New Haven area to prepare young men “for service in church and civil state.” Yale’s graduates had included missionaries of the Gospel for a century and a half before Dwight Hall was ever built.

Henry Burt Wright ‘98 produced a review published in 1901 as Two Centuries of Christian Activity at Yale. Dwight Hall’s own namesake, President Timothy Dwight, had prayed for revival at Yale for seven years. The revival that finally ensued and so changed Yale in 1802 was the first of five revivals Dwight was to see in his last 16 years as Yale’s President.

The following years Yale University experienced ebbs and flows of Christian activity involving professors and students. However, the 1880’s were the beginning of a new order in the religious life on campus. The customary religious activities continued, but there was a greater earnestness and fresh efforts in prayer meetings, Bible studies, and voluntary Christian work.

The students themselves took the initiative in this new movement, though not without the supporting counsel of Christian faculty and alumni. In 1879, Dill Boomer ‘80 had the idea of the Yale Christian Social Union (YCSU), inspired by a YMCA meeting he attended in Baltimore. With three friends, and advised by Professor Cyrus Northrup, he planned and began a voluntary Christian organization on campus. Beyond the weekly class prayer meeting, they aimed to strengthen the relationships among the Christians in the four classes through a monthly Sunday meeting, and to challenge the freshman class to purposeful Christian service. Attendance at the individual class prayer meetings averaged in the thirties out of a class of about 140.

After the YCSU merged with the YMCA in 1881, students began many lines of Christian work that changed the campus and the community. Wright notes that Bible studies were “foremost… in so far as depth of influence is concerned.” The Bible studies became more organized, so that students were systematically learning about the teachings of Christ; yet they were expressly devotional and practical in nature. The Christian activities grew out of the desire and commitment to put Christ’s teachings into practice.

Practical Christian service often transformed the theory into personal understanding. Wright wrote, “A college man, although he is supposed to be undergoing a training calculated to fit him for the duties of life and contact with men is nevertheless, almost entirely deprived of the latter unless he takes pains to reach out of his own little world in which he is for the time being situated. When he attempts to lead other men to Christ the meaning of his own religion is forced upon him, Christianity ceases to be a theory and its value in the transformation of character and the saving of men is forever graven on his mind.”

He also wrote about the benefits of working in City Rescue Missions to help the under-privileged, drunkards, or homeless. “Where before [a person] may have thought lightly about drinking and sins of a worse nature, after he has been fighting these sins all one year in the mission, he cannot, knowing to what depths they may lead a man, feel lightly towards them again.”

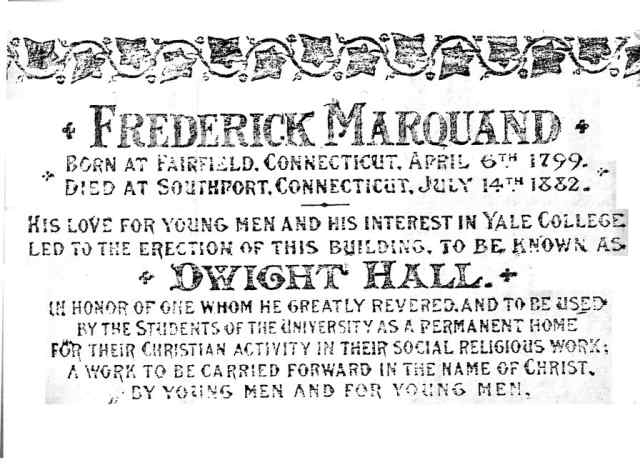

With more activity, the students felt a growing need for a central meeting place to coordinate their Christian work—one that would include offices, a library, and assembly rooms. Just as Murray Hall had been built for the YMCA in Princeton in 1879, students proposed to the Yale Corporation a similar building as a center for religious activity on the campus. President Noah Porter said that the erection of the building “would be hailed by the best friends of the college as full of promise and blessing.” With his support, and through gifts from alumni Frederick Marquand and Elbert B. Monroe, the building of Dwight Hall began in July 1885 and was dedicated the following year.

So the movement arose, and the original Dwight hall was built to aid and forward it. But the life of any authentic spiritual movement is not found in a building, or an organization. It is the lives of such students who lived out their faith convictions in practical service. They took to heart Christ’s command, “Seek first His kingdom and his righteousness.” From Dwight Hall, fruitful service sprang, not from general humanitarian impulse, but from a central devotion to Jesus Christ.

As one who spent my Yale undergraduate years as a believer, I see some parallels between these students of a century ago and the Christians on campus today. They met, prayed, studied the Bible together, and tried to help people in various ways.

I see some differences, too. The students in Dwight Hall had ideas that could be taken up again with real blessing. They took up the missionary call of the Great Commission, and got involved in inner-city work in New Haven, for Jesus’ sake. They visited high schools and prep schools to talk with seniors about serving Christ in college years, and visited Christians on other college campuses to encourage each other and stand together.

Most of all, I was struck by the way those students discarded the “every-man-for-himself” attitude that is so easy to adopt. They decided to care about each other, about their classmates, about their campus and city.

When they did, God met them—right on the Old Campus—and used them to transform Yale and the world into a better place.

Yuna Lee, Saybrook ’94

© 1997 The Yale Standard Committee

Sources:

Reynolds, Fisher, and Wright (eds.): Two Centuries of Christian Activity at Yale, 1901.

George Stewart (ed.): Some Annals of the Yale Christian Association, 1937.

Dwight Hall photo credits:

Courtesy of Yale University Picture Collection, YRG 48-A-43, Box 21, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.