Pioneers of Missions and Telecommunications: Yale’s Amazing Morse Legacy |

Inventor Samuel F. B. Morse was discouraged. He had spent the entire winter of 1843 trying to win a Congressional appropriation to fund the construction of an experimental telegraph line. Though Morse had given eleven years to perfecting the telegraph, and was convinced that it was destined to make instant communication between all parts of the globe a reality, to many congressmen his machine seemed no more than an elaborate hoax.

In legislative debate, some representatives had suggested that if the telegraph were to be funded, there ought to be an appropriation for experiments in mesmerism, too. The House had barely passed Morse’s bill, 89 to 83: seventy congressmen had abstained from voting to escape responsibility for spending public money on something they didn’t understand.

Now, on March 3, the final day of the legislative session, more than 140 bills stood in line ahead of Morse’s on the Senate calendar. Highly placed friends told the inventor to prepare for disappointment, as there was little chance his bill would be taken up. After paying his hotel bill at the end of the day, Morse discovered that he had enough money to buy his rail ticket home to New York, and only 37 and ½ cents more. He went to his room, and, having poured out his fears and concerns to God, slept like a child.

The next morning before breakfast, a servant called to tell him a young lady was waiting to see him. It was Annie Ellsworth, daughter of the U.S. Commissioner of Patents, and she congratulated him warmly on the passage of his bill. He assured her she must be mistaken, but she insisted that her father had seen the President sign his name to the bill.

So astonished he couldn’t speak, Morse eventually blurted out, “Annie… I am going to make you a promise; the first dispatch on the completed line from Washington to Baltimore shall be yours.” Morse kept his promise, and Annie’s choice was the last phrase of Numbers 23:23:

Statue of Samuel F. B. Morse,

in Central Park, New York City.

Surely there is no enchantment against Jacob,

Neither is there any divination against Israel.

According to this time it shall be said of Jacob and of Israel,

“What hath God wrought!”

“What hath God wrought” stayed with Samuel F. B. Morse as an exact expression of his own sense of how the telegraph had come into being. After the Washington-Baltimore line was completed in 1844, Morse wrote to his brother Sidney:

“You will see by the papers how great success has attended the first efforts of the Telegraph… ‘What hath God wrought!’ It is his work, and He alone could have carried me thus far through all my trials and enabled me to triumph over the obstacles, physical and moral, which opposed me.”

By 1874, thirty years after the experimental line was built, the worldwide communications network Morse had envisioned had become reality, with 650,000 miles of telegraph wire and 30,000 miles of submarine cable connecting cities across the globe. Characteristically, Morse had given the first $25 he had earned from the telegraph to a Sunday school. One of the last acts of his life was to endow a lectureship on the relation of the Bible to the sciences.

Modern writers might be tempted to view Samuel F. B. Morse (Yale, 1810) as a notable inventor and artist possessed of an odd religious quirk, yet Morse’s faith in Christ was not incidental, but central to his life. A look at the Morse family and their connection to Yale reveals the spiritual sources of his vision and labors.

Jedidiah Morse (1761-1826)

Samuel’s father, Jedidiah Morse, was a country boy from Woodstock, Connecticut, who attended Yale during the American Revolution. In the middle of his college career, a spiritual awakening came to Yale. Jedidiah fell under conviction of sin, and, in the spring of 1781, gave his life to Christ.

Coming to Christ seems to have energized him in all parts of his life, and the volume and variety of his activity thereafter is astonishing. To his friend Yale President Timothy Dwight (1752-1817) he seemed “as full of resources as an egg is of meat.” Daniel Webster said Jedidiah was “always thinking, always writing, always talking, always acting.” Though his body was weak, Jedidiah’s motto, Samuel later remembered, was “better wear out than rust out.”

After his graduation in 1783, Jedidiah stayed in New Haven to prepare for the ministry, studying with the help of Jonathan Edwards, Jr. He also taught a school for girls, and, recognizing the inadequacy of the textbooks available in America at the time, compiled and published the first American geography. He and his sons produced many editions of this and other texts, and his works were the standard geographies for schools and colleges in the United States until about 1850.

Because they met a need for reliable information about the physical conditions of the United States, Morse’s books sparked a wave of immigration to America and made their author world famous. Jedidiah’s tombstone in Grove Street Cemetery is topped with a stone globe, and he is still remembered for his work as a geographer.

Most of Jedidiah’s buoyant energy, though, went into pioneering new ways to extend the reach of the gospel. Many of his initiatives gave birth to evangelistic institutions that Americans take for granted today. For instance, tract societies in America are a direct product of a missionary tour Morse took to the developing settlements in Maine. Everywhere he went he found few Bibles and little knowledge of Christ.

Recognizing the spiritual destitution of the frontier, Jedidiah went home and bought fifty-five reams of paper, with which he printed over 32,000 tracts for distribution in Maine, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The stable behind his parsonage in Charlestown, Massachusetts, became the first tract depot in the United States, and the New England Tract Society that formed because of his efforts was a direct precursor to the enduring American Tract Society.

Jedidiah and his sons started the first Sunday school in New England. (The family continued this kind of work when they moved to Connecticut; Samuel F. B. Morse became the first Sunday school superintendent in New Haven.) Jedidiah also helped found the American Bible Society, and he was a key member of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, in an age when even some Christians regarded missions as dubious and extravagant.

When in 1812 America’s first band for foreign missionaries found their entry into India blocked by British suspicion that they were part of a political plot, Morse refused to despair of the mission and wrote to his friend William Wilberforce for help. Though the great English abolitionist expressed little hope for change in the situation, his intercession was successful, and the ban on American mission work was lifted. Morse’s simple letter had helped tip the spiritual balance.

All his life, Jedidiah loved Yale and made a point of attending every commencement. Probably because he himself had been saved at Yale, his concern for the spiritual welfare of the college was strong. In 1802 he heard that revival had come to Yale and wrote to President Timothy Dwight for confirmation. Dwight’s response is preserved in Sterling Library’s manuscript collection. It details God’s work among the students, stating that in the period from March to July 1802, no fewer than sixty-seven had come to Christ. By September when Jedidiah attended commencement, he could write home to his wife that the number had risen to eighty. (The entire student body then was about 160.)

As pastor of the First Congregational Church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, Jedidiah was a member of the Harvard Board of Overseers. Not long after the Yale revival he found himself in a losing battle to keep Harvard operating upon solidly Biblical foundations. In 1805, a majority of the Harvard Board elected Henry Ware, a Unitarian, to the Hollis professorate of Divinity. Seeing the need for a spiritually sound institution of higher learning to take Harvard’s place, Jedidiah brought all the separate strands of the Christian community in New England together to found Andover Theological Seminary. He also started a monthly journal called The Panoplist, whose mission was to assert and uphold Biblical truth.

Out of Andover’s first graduating class came America’s first foreign missionaries, and the school became known as a missionary training ground. The Panoplist later became The Missionary Herald, which recorded the progress of American missionary activity around the world. Morse paid the price for his opposition to Unitarianism, though: it was probably the decisive factor in his 1819 loss of the pastorate in Charlestown.

Though there isn’t space here to fairly represent the amazing fruitfulness of Jedidiah Morse’s life, it should be noted that he was an abolitionist and friend of the black community in Boston when abolitionists were few. Also, a significant portion of his life was spent looking for ways to benefit Native Americans and preparing the way for missions among them.

As U.S. Commissioner to the Indian Tribes (1820-1822), the then feeble old man undertook a 3,000-mile trip to survey the state of the Northern tribes. While in Green Bay, Wisconsin, he uncovered the attempt of an Indian agent to concoct a false treaty, which would have defrauded the Menominee tribe of a valuable part of their lands. Because of Morse’s information, the Senate refused to ratify the treaty, and the agent’s ploy failed.

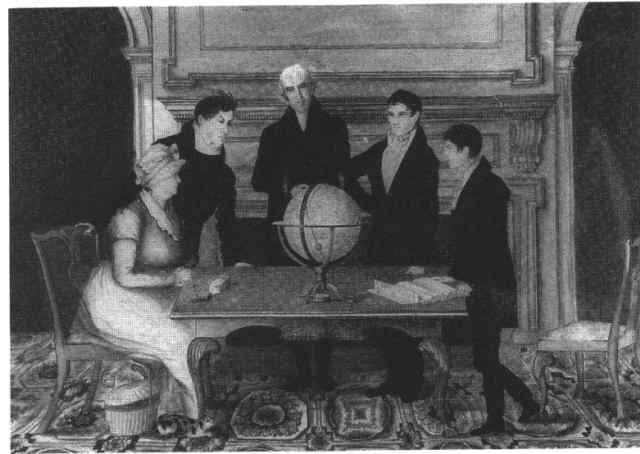

Samuel F. B. Morse’s portrait of his family (ca. 1809)

While official Washington chose to ignore many of Morse’s recommendations regarding the tribes, his Native American advocacy was carried on to some extent by his associate Jeremiah Evarts (Yale, 1802), secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Evarts fought valiantly to stop Andrew Jackson’s forced removal of the Cherokee, though he died before the tragedy known as “The Trail of Tears” took place.

Orphan John Todd once described the Morse household as a place from which he went away “in tears, feeling that such a home must be more like Heaven than any which I could conceive.” The joy of Christ was rich in Jedidiah’s life: his son Richard remembered his father hearing the sound of bells from the tower of Christ Church, Boston, and taking up the notes to shout aloud the hymn:

Oh could I soar to worlds above,

The blest abode of peace and love.

Jedidiah’s sons

The three Morse brothers, Richard, Sidney, and Samuel F. B., the oldest, were close observers of their father’s dynamic faith, and each become a vital, active Christian in his own right. All the brothers, and several of their sons, graduated from Yale.

Building upon his father’s pioneering journalism, Sidney started The Boston Recorder, a weekly paper. Both Richard and Sidney then moved to New York, and in 1823 began The New York Observer, which in time became one of the most important weeklies in the United States. The Observer persisted into the twentieth century as an evangelical voice in the nation’s press, and Morse grandsons took it up when their fathers became too old to carry it forward.

Samuel F. B. entered upon adult life as an artist. Some of his earliest portraits provided him pocket money at Yale, and others went to help pay his term bills. He became one of the small handful of important American painters in his generation, and many famous depictions of notable Americans are his work. The portrait of Noah Webster at the front of many Webster dictionaries is his, as are the most familiar portraits of Benjamin Silliman, Eli Whitney, and General Lafayette. One of his most striking studies is a portrait of pioneer missionaries to Hawaii, Hiram and Sybil Bingham.

Morse the artist also became known as “the Father of American photography.” He was one of the first in the United States to experiment with a camera, and he trained many of the nation’s earliest photographers. His best pupil was Mathew Brady, who achieved national fame as photographer of the Civil War.

Artist Samuel F. B. Morse, for whom Morse College is named (self-portrait, ca. 1809)

Out of failure came Samuel’s greatest success. In 1836 the United States Congress was looking for artists to paint historical murals in the Capitol Rotunda. Morse, then President of the National Academy of Design, had many impressive works to his credit, and was an obvious choice. He had always aspired to be an historical painter, and he stood very much in need of money. Morse’s hand-to-mouth existence as an artist had made it difficult for him to support his motherless children (his wife had died in 1825), and he longed to provide a secure home for them.

In February 1837 came the stunning news that because of the prejudices of John Quincy Adams, Morse had not been chosen. This dealt a death blow to his life as a painter.

Yet God was not finished with him. His electromagnetic telegraph was at first an attempt to win a secure income so he could support his children and continue painting, but it eventually became his life’s work. During the eleven years he spent developing the telegraph, he sometimes went without food to get money to buy parts for it. People sneered at his “thunder and lightening jimcrack.” But his years of privation ended in 1844 with the Congressional appropriation to build a trial telegraph line.

The telegraph began a communications revolution that has not yet ended. It made possible a centralization of American business and gave rise to the large corporate structures with which we are so familiar today. News from around the world became instantly available by telegraph, and the modern press was born. The telegraph is now considered one of the ten most important inventions ever, because it was the first to make practical use of electricity.

Tom Standage, in his book, “The Victorian Internet,” has pointed out that the Internet is in many respects a modern elaboration of the telegraph. The ITU (International Telecommunications Union), which sets the protocols for computer communication, began as the International Telegraph Union. The telephone, which largely displaced the telegraph, was itself invented because Alexander Graham Bell was looking for a way to increase traffic on a telegraph line.

In 1871, a few months before Samuel F. B.’s death, a statue of him and his telegraph was unveiled in Central Park. He told his daughter that if such a memorial was to be erected, he wished it would have inscribed upon its base the scripture “Not unto us, not unto us, but to God, be the glory,” and with that the first telegraph message, “What hath God wrought!”

Marena Fisher, Graduate ’91

© 2000 The Yale Standard Committee

See below on Richard Cary Morse.

- Sources:

- The Life of Jedidiah Morse by William B. Sprague, New York, 1874.

- Jedidiah Morse: A Champion of New England Orthodoxy by James K. Morse, New York, 1939.

- Samuel F. B. Morse: His Letters and Journals ed. by Edward Lind Morse, Boston, 1914.

- The American Leonardo: A Life of Samuel F. B. Morse by Carleton Mabee, New York, 1943.

- The Victorian Internet: the Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s On-line Pioneers by Tom Standage, New York, 1998.

- My Life with Young Men: Fifty Years in the Young Men’s Christian Association by Richard C. Morse, New York, 1918.

Richard Cary Morse (1841-1926)

Richard Cary Morse, grandson of Jedidiah Morse and nephew to Samuel F. B. Morse, graduated from Yale in 1862 without any firm sense of what he should do with himself.

Family members encouraged Richard to take a position on the staff of The New York Observer, a weekly newspaper the Morse clan had run for several decades. One of Richard’s first assignments for the paper was to cover a New York convention of the infant YMCA, a Christian youth ministry just beginning to take off in the United States.

Richard’s article so impressed YMCA leader Robert McBurney that he asked him to sign on to the ministry’s staff. In 1872 Morse became first General Secretary of the YMCA in charge of the group’s international operations. He continued to wholeheartedly serve Christ till his death in 1926.

One desire of Morse’s heart was to strengthen spiritual life at Yale, and he suggested to students that they themselves should take up the burden of campus ministry. Morse’s plea at first landed on deaf ears. But D. L. Moody’s visit to New Haven in 1878 led to many conversions at Yale, and some of those converted were then ready to heed Morse.

Student initiatives led to the founding of Dwight Hall, the first collegiate YMCA in the United States. Above the entrance of the first Dwight Hall building was the inscription in Greek “One is your master, even the Christ.” (Matthew 23:10)

1 Reply to “Samuel F. B. Morse”

Comments are closed.