Timothy Dwight and Yale: The Making of a University |

Few men have poured out as much for Yale as did Timothy Dwight. He was a prodigious scholar, a brilliant educator, and an educational reformer far ahead of his time. He was the chief architect of Yale as a university. And Dwight was a powerful revivalist who helped usher in repeated spiritual awakenings at Yale during his 22 years as president, and this at a time when apostate philosophies had all but destroyed faith on the campus.

Anyone who seeks the good of Yale would do well to study Timothy Dwight’s life. He carried in his bosom the vision of the school at its academic and spiritual best, and labored tirelessly to see the vision fulfilled.

Early Years

Pedigree alone would have made Dwight’s birth notable. He was born on May 14, 1752 to the third daughter of Jonathan Edwards, the great theologian and revivalist of America’s First Great Awakening. Mary Edwards Dwight daily immersed Timothy, her eldest, in catechisms, Bible stories and doctrine. Since no public schools existed at that time, she was Timothy’s (and his twelve siblings’) school.

On his father’s side, Timothy came from a venerable line of public servants, judges, militia captains and lawyers. The Dwights were noble, if not by title in the New World, then by conduct, and their family name was associated by all with public service and integrity.

It didn’t take long for Mary Dwight to discover her eldest had an unusually quick mind. By age four, Dwight was reading the Bible, songbooks, books on prayer and whatever else his mother gave him. At the age of six, the precocious Dwight would overhear Latin lessons given to older boys at a local grammar school, and then steal away on his own to go over Lilly’s Latin Grammar. He had a remarkably absorbent mind, and not infrequently surprised adults by recounting stories he had read, with all the minutiae included.

Christianity is a system of restraint on every passion, and every appetite. Some it forbids entirely; and all it confines within limits, which by the mass of mankind, both learned and unlearned, will be esteemed narrow and severe. Philosophy, on the contrary, holds out, as you have already seen, a general license to every passion and appetite. Its doctrines therefore please of course; and find a ready welcome in the heart.

Dwight progressed so rapidly as a student, it was expected that he would be ready to enter Yale by the age of eight, at half the age of the typical freshman. However, the preparatory school he was attending closed down, delaying his academic progress. The fields of learning in New Haven would have to wait five years.

In 1765, at the age of thirteen, Dwight nervously faced his college entrance examiners and displayed, to the great pleasure of his hearers, his grasp of Tully, Virgil and the Greek Testament; his ability to write Latin prose; his understanding of arithmetic; and that he had a “suitable testimony of a blameless life and conversation.” He was in.

Dwight’s days at Yale were marked by grueling self-imposed discipline. His effort earned him valedictory honors at his graduation and an appointment as a tutor of the undergraduates.

In that role, Dwight spent every free hour conquering new fields of study. At one period, mathematics and the infant field of physics became his passion. At another period, it was poetry. Never one to shy away from a subject, Dwight decided to try his hand at writing epic poetry after the style of Milton and the classical poets. The eventual result was The Conquest of Canaan, which told the story of the Jewish people’s victorious march into God’s promised land.

All this effort—as a scholar, tutor and administrator—took a toll, however. Studying night after night by meager candlelight, Dwight ruined his eyes. Furthermore, by the second year of his tutorship, his health failed, forcing him to quit his habitation of books indefinitely.

But this was Providence at work. His weakness brought him close to death and forced him to recognize his mortality, even though he was only 21. Suddenly, the Scriptural lessons and stories he had known from childhood spoke to him as they had never done before. He recognized he needed God’s salvation, and sought to obtain assurance of it. Early in 1774, comfort came to his heart. He yielded his life to the Creator, pledging himself to be an instrument for divine purposes in the hands of the Master Craftsman. Dwight stepped out from this experience with a new set of motivations.

Revivalist President

By 1795, Dwight had distinguished himself as a scholar, educator, writer and citizen, and became the obvious choice to succeed the recently deceased president of Yale College, Ezra Stiles.

Dwight was inaugurated September 8, 1795, and the challenges began immediately. What confronted him on the campus was not pleasant. The Yale of the post-Revolutionary War years was far from the uneventful place of universal Puritan conformity it is commonly thought to have been. British and French soldiers brought to American shores not only their military might but also the worst of the Old World’s cynicism and loose morals.

Students found pleasure in nightly revellings that frequently included breaking tutors’ windows and smashing bottles. Yale men regularly clashed with drunken townsmen in violent engagements where rocks flew and clubs flailed.

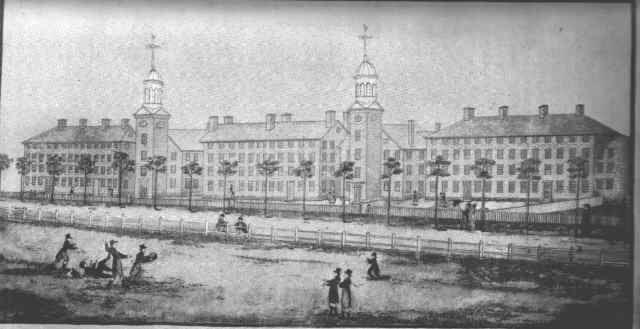

Yale College in 1807, from an engraving by Amos Doolittle. Far to the right, President Dwight in spectacles watches the students playing football. (Courtesy Yale University Library.)

Christian faith was unfashionable and reviled on campus. Voltaire became Yale’s “prophet,” and “reason” her watchword. Caught up in the fervor of the age, students renamed themselves after French philosophers, addressing each other as “Classmate Diderot” and “Sophomore D’Alembert,” for example. Harvard had succumbed to rationalism long ago, and it appeared inevitable that Yale would follow suit. But for Dwight, it most likely would have.

In Dwight’s mind, all his effort as president was worthless if those he nurtured left Yale intellectually filled but spiritually poisoned with soul-destroying philosophies.

Something rose up in Dwight as he faced this hostile challenge from across the Atlantic. When the senior class decided to test their new instructor by suggesting they debate the question, “Are the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament the Word of God?,” Dwight, to their utter amazement, picked up the gauntlet.

With academic rigor he refuted the popular arguments against the reliability of Scripture and submitted his reasons for believing it to be the revelation of God. With a rhetorical knife sharpened by faith and years of diligent study, he cut through the seductive abstractions of the French philosophies, and demonstrated to their devotees the unreasonableness of what they had embraced.

In the classroom, he reasoned, and in the pulpit, he pleaded. Cold hearts began to thaw at his words as snow melts in the face of a steady spring sun. In 1802, his eyes saw what his heart so yearned for. A religious revival swept across the campus, and nearly 80 of the 230 students at the school were converted to Christ. One of those stirred was Benjamin Silliman, who recounted in a letter to his mother:

“Yale College is a little temple: prayer and praise seem to be the delight of the greater part of the students, while those who are still unfeeling are awed into respectful silence.”

The event was extraordinary. Religious revivals were no more commonplace on college campuses then than they are now. Students were no less prone to rebellion and hostility to faith in Christ. Harvard, which had given up the guidance of Scriptures long before, remained cold throughout the early 1800s while Yale was being touched again and again with spiritual awakenings.

Another revival visited the campus in 1808. Yale had sunk on spiritual matters since the first revival, so that only 15 believing students remained on campus. Heavily burdened one Sabbath day, Dwight preached to his students one of the most passionate sermons of his life. “Young man, I say unto thee Arise!” was his challenge, and conviction fell on Yale once more.

In 1812-13 another revival came in which almost one hundred students gave their hearts to Christ. A fourth came in the spring of 1815, this one sparked by a group of students who gathered at 3:30 every morning to pray for the campus. One of the students was a convert from the previous revival, and later remembered these cold winter mornings of prayer as among the happiest of his life. Another student, who could not keep all the blessings he received to himself, happily carried a contagious faith to the Dartmouth campus, where afterwards, a revival ensued.

These awakenings were rescue and preservation for a campus which seemed intent on abandoning its Christian heritage. Hearing Dwight’s prayers, God saw fit to smile on Yale and continue stoking the spiritual coals that would fuel the school’s rich student missionary activity throughout the nineteenth century.

Dwight’s labors were not confined only to the Yale campus. He became recognized nationally as one of the most able defenders of Scripture, and judges, senators, lawyers, and wealthy laymen from various parts of the country came to hear him preach.

One such visitor wrote of Dwight, “[He is] methodical, eloquent, ingenious, forcible, and in language chaste, extremely energetic, he commands universal attention from his audience.”

Dwight’s discourses against the new philosophy were published in pamphlet form and distributed widely. He also published hymnals and founded missionary societies to further the cause of Christ.

President of Yale

The testimony of what Dwight did for students’ souls is inseparable from his achievements as the school’s chief administrator. Both labors sprang from a single source: his desire to see God’s purpose for Yale fulfilled.

It can be argued that no man is more responsible for making Yale the great institution of learning it is today than Timothy Dwight. His predecessor, the brilliant Ezra Stiles, led the school through the turmoil of the revolutionary years, and brought it to a tolerable state. But his gift was not administrative, and the school suffered from serious disciplinary problems and financial constraints by the time of his death.

With a flair for politics, Dwight set out early on to establish good will with the Connecticut state legislature, with which relations were often strained. Dwight prevailed upon legislators, who were wont to view Yale as a snooty preserve of high-minded academics, to consider her with pride and as the training ground for the state’s ablest and best.

The new President was not above pointing to a particularly well-funded rival in the Boston area to put Yale’s sometimes sorry condition in high relief. Under his persuasion, the state legislature opened up its coffers to the growing institution and provided funding in a time of critical need. The leaky roof of the chapel and the decaying structure of Connecticut Hall could finally be repaired.

Much of these funds were used to increase Yale’s library holdings. In 1795, Yale had a meager 2,700 volumes, a total which had remained static for over sixty years. Harvard had 13,000—motivation enough! Over his tenure, Dwight saw the library grow to a quality collection of 7,000 volumes, and later said, “Few libraries are probably more valuable in proportion to their size.”

Today, the number of academic programs at Yale is immense, but it was not always so. By the end of President Stiles’s term, only two professorships existed: the Professorship of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy, and the Professorship of Divinity, both of which were being filled by the president himself. He and a handful of tutors ran the whole Yale program. Though Stiles envisioned the addition of a law school and medical school, his hands were tied by constraints caused by the war.

Dwight readily assumed the burden of his predecessor’s vision to expand Yale’s curriculum.

In 1801, Dwight received approval from the Corporation to hire a professor of law. Thus was planted the seedling that would become the Yale Law School. Then in 1802, the Corporation authorized Dwight to fill two newly created professorships, that of Languages and Ecclesiastical History, and Chemistry.

To the Chemistry chair he appointed a young tutor named Benjamin Silliman. Dwight persuaded Silliman to abandon his aspiration to become a lawyer and turn his efforts towards the then-infant field of chemistry. Silliman soon became “father of American scientific education” and caused the sciences to flourish at Yale and in America.

In 1811, after a protracted struggle for funding and faculty, Dwight saw the Medical Institution of Yale College established.

Dwight also laid the groundwork for the Yale Divinity School, which was established five years after his death. He intended it to be a bulwark against the infidel philosophies then threatening the country.

Dwight saw earlier than most what Yale was to become. With ceaseless energy he carried his vision through his days as President and applied all his administrative, political and rhetorical skills to bring it to fruition.

Sunset in Glory

On January 11, 1817, after over two decades of relentless activity for his Lord at Yale, Dwight passed into the hands of his Savior, an event which his old friend Jedidiah Morse graced with the words, “[Dr. Dwight’s] death is a public loss and will probably be more extensively felt than the death of any other man in our country. His sun has set in its full glory.”

It is hard to capture all the specifics of the life of this tireless laborer; he worked hard, and accomplished much. But the wellsprings of his life one can more readily identify: he loved his Savior, and the students entrusted to him. These motives set his life in motion, and Yale, and indeed the nation, were profoundly affected.

Stephen J. Ahn, JE ’96

© 2001 The Yale Standard Committee